“People do better with truth than without it.”

I first heard that line on an American TV show, Couples Therapy. It struck me as so simple, so obvious, yet so rarely honoured in practice.

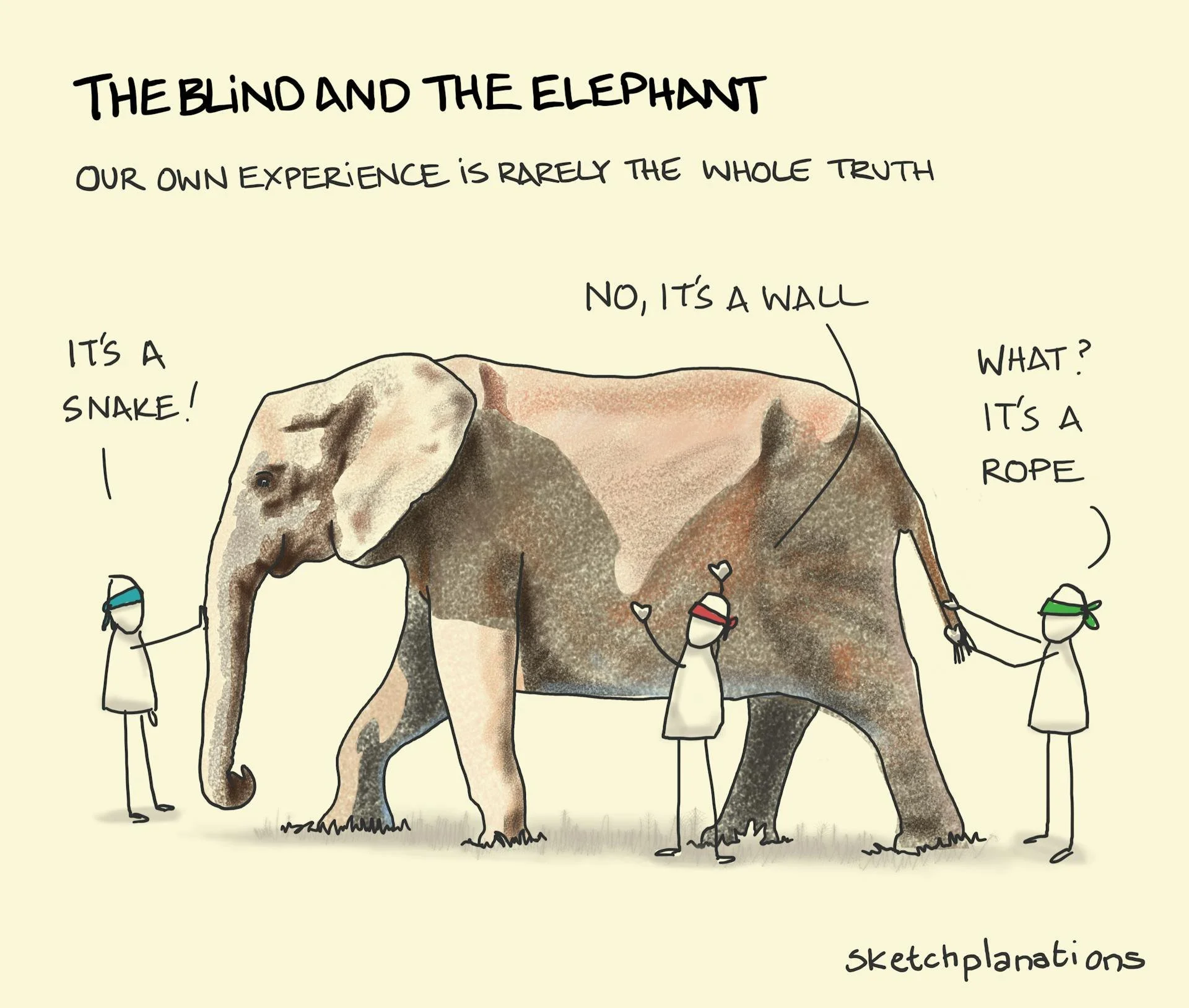

What happens when the elephant in the room is ignored for too long?

Truth doesn't always deliver comfort or certainty. Sometimes it reveals fragility, invites conflict, destabilises what we'd rather keep stable. But silence, ambiguity, or lies? They corrode trust slowly, invisibly. Sadly, the cost to organisations is steep: disengagement, stifled innovation, internal fractures, and ultimately, loss of legitimacy.

Leaders (in families, teams, organisations) forget this at their peril. Because in the end, people do better with truth than without it.

The Business Case for Truth-Telling

1. Trust drives performance.

When people sense a mismatch between what leaders say and what they do, trust erodes. Relationships stiffen. Conversation narrows. Performance suffers. Research consistently shows that high-trust organisations outperform low-trust ones on every metric: retention, innovation, profitability, and speed of execution. Truth-telling, even when painful, builds credibility and preserves human dignity.

2. Truth enables adaptation.

In complex environments, we don't have perfect foresight. If we mask reality to preserve appearances, we blind ourselves to feedback. When we face truth, even messy, hard to hear truth - we can course-correct, learn, and adapt. Organisations that can't tell themselves the truth can't respond to change.

3. Truth-tellers become organisational anchors.

People respect, forgive, and support those who speak truth, including leaders who say "I don't know" when they genuinely don't. Truth-telling signals both integrity and vulnerability, which are magnets for engagement and loyalty.

4. Yet our systems push against it.

Here's the tension: reputation risk, stock prices, social media backlash, performance expectations… all these push leaders towards polished narratives, ambiguity, and spin. The systemic pressures are real. Silence or distortion often feel safer in the moment.

However, I believe that over time, the system suffers more from the rot of untruth than from the short-term discomfort of honesty.

What Happens When Truth Dies

Consider BrewDog, a company that explicitly champions doing "business differently": ethical, community-minded, bold. When over 200 former employees wrote a public letter claiming that staff were overworked, undervalued, and discouraged from dissent, the gap between brand story and lived reality became catastrophic. The ethical narrative collapsed under the weight of employee testimony.

Or Uber. A brand promising safety, agility, and customer-centred innovation faced scandal after scandal: harassment, discrimination, abuse of power, suppression of whistleblowing. For many insiders, the "hustle culture" rhetoric masked serious dysfunction. The officially sanctioned narrative bore no resemblance to what people actually experienced.

These aren't isolated failures. They follow a pattern.

Ethnographic research at a German subsidiary of Bosch found that when the organisation’s official identity story diverged from employees’ lived experiences, people began to withhold, shade, or reframe their accounts internally. Over time, this dissonance undermined identification, loyalty, and advocacy. Employees became reluctant to speak openly, and the gap between the official narrative and lived reality corroded internal legitimacy

What's revealing about these examples is this: organisations that enforce officially sanctioned lines of discourse, often see this strategy backfire spectacularly. Stifled dissent and suppressed feedback don't disappear. They accumulate. Eventually, they boil over, and those safe narratives are replaced by a far messier reality, often at the worst possible moment.

When organisations don't make space for voices that diverge from the preferred narrative, truth goes underground. Then, over time, the internal culture warps.

Leading with the Truth

Truth-telling doesn't mean reckless confession or oversharing. It means disciplined honesty; the kind that respects tension, risk, and real-world constraints, but doesn't coil into silence.

Here are practices leaders can adopt immediately:

Say "I don't know" when you don't.

It signals integrity and invites others into problem-solving. On Monday morning, when someone asks about the timeline for a decision, try: "I don't have clarity on that yet, but here's what we're working through" rather than offering false certainty.

Create safe spaces for dissent.

Actively encourage people to share views that challenge the dominant narrative. Structured forums work: pre-mortems, honest retrospectives, team meetings where unpopular views are not just tolerated but protected and acted upon.

Check the story gap.

Compare your "official story" with the stories your people actually tell. If there's daylight between them, pay attention. Use surveys, listening sessions, or simply ask: "What's the gap between what we say and what you experience?"

Hold small truths daily.

Truth doesn't always need grand statements. It lives in "Yes, I messed that up," "Thanks for pointing that out," or "We're behind schedule and here's why." These micro-acts build resilience and make it safe for others to tell the truth too.

Why This Is Pragmatic, Not Idealistic

Truth-telling can feel risky. But avoiding truth is riskier still. Spin and silence may protect you today, but they erode you tomorrow. Truth-telling keeps organisations adaptive, cohesive, and capable of facing complexity.

Short-term risk versus long-term decay.

Whilst truth can provoke backlash, slow outcomes, and create discomfort, systematic untruth accelerates decay; disengagement, internal fractures, loss of legitimacy. The question isn't whether truth is comfortable. It's whether you can afford its absence.

Truth as complexity, not binary.

We often think "truth" must mean perfect clarity. However, in organisations, truth is usually partial, evolving, contested. Honouring that complexity, acknowledging what we don't know, what's shifting, what's uncertain, is itself an act of truth-telling.

Organisational Adaptation demands it.

In volatile environments, organisations that avoid their shadows (hard data, difficult feedback, internal conflict) lose agility. The capacity to face reality is the capacity to respond.

This is not a naive call for unguarded confession. It's a call for disciplined honesty - the kind that builds adaptive, resilient, high-performing organisations.

Leaders, remember: people do better with truth than without it.

*Full citation: Zinkstein, K. (2018). Telling Stories: the Link Between Organisational Identity, Culture and Employee Advocacy [Doctoral thesis, University of Westminster]. WestminsterResearch. https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/q9xy8/telling-stories-the-link-between-organisational-identity-culture-and-employee-advocacy

Read more articles…